Our latest books are Katamari Damacy and Shovel Knight. Click through to learn more.

Come see us October 20-21 at the Porland Retro Gaming Expo. Meet Boss Fight's editor/Bible Adventures author Gabe Durham and Final Fantasy V author Chris Kohler.

We now have audiobooks! Chrono Trigger and Bible Adventures are available now on Audible.

Six of our books are now out in French. You can pick them up from Omake Books.

7/26 - Los Angeles: Boss Fight Books: Season 4 Launch Party Funtimes

- Alyse Knorr (Super Mario Bros. 3)

- Daniel Lisi (World of Warcraft)

- Jarett Kobek (Soft & Cuddly)

- Brock Wilbur (Postal)

8/10 - San Francisco: Boss Fight Books Presents: Kingdom Hearts II Release Party

- Alexa Ray Corriea, author of the new Kingdom Hearts II

- Nick Suttner, author of Shadow of the Colossus

- Chris Kohler, author of the forthcoming Final Fantasy V

9/1 - PAX West (Seattle) Panel

Details forthcoming. Alexa Ray Corriea, Nick Suttner, Chris Kohler, L.E. Hall, Gabe Durham.

One of our favorite Kickstarter traditions is the "gamer profile tier," in which one of our authors interviews a Kickstarter backer. Today, Alyse Knorr (author of Super Mario Bros. 3) interviews Alraz.exe about his gaming history.

Enjoy! - BFB

Alyse Knorr: What is your favorite game and why?

Alraz: This is a very tough one, but after much consideration, I'll go with Mega Man 3 on the NES. The main reason why it's my favorite game is because it's the Mega Man game I played the most as a kid. Though I never owned the game back then, a friend of mine had it and I used to borrow his copy and play it all day long.

I know is Inafune-san's "least favorite" of the whole franchise because of all of the things that went behind it's development, but as a kid, I was completely unaware of any of that and couldn't care less. The game was awesome. It had very addicting music and a kind of mystic dark mood to it that rather than scare you away, it lures you into it, makes you wonder "what's in there..?"; and my Gosh, you are in for quite a ride! Even to this day, I feel that Mega Man 3 has the best and most nostalgia-inducing credits music.

A few other runner-ups for the title of "top favorite game" would be: Marvel vs Capcom 1 and Diablo 2. Those games stole so many years of my youth ^_^"

What was the first game you fell in love with?

This was definitely Mega Man 2: My first Mega Man game ever. I was like 7 years old when I first played it; was not aware of the first one, but it didn't matter. Mega Man 2 was so different to anything I had played until then, with it's colorful visuals, it's lively music and the fluid and responsive controller. Of course, back in the day I had no clue that those were all elements that were drawing me into the game, all I knew was that, even though I kept dying over and over again, I was really enjoying it.

It was so powerful that it eventually led me into taking a career in computer science because I wanted to know how these games were made. I wanted to make them myself.

I owe so much to this inspiration: I come from what in my country we would call "a humble background", which is just euphemism for "a poor family", but I liked these game so much that I couldn't stop. I had to learn more. Today, I owe my professional career to the inspiration that Mega Man games in general gave me; I loved them so much as a kid, and that love kept feeding my curiosity and that curiosity eventually led me to learn about computers and programming. Had there been no Mega Man, I would not be talking to you right now about my favorite anything, I would probably be a low level employee at a department store or something like that...

As a homage to that inspiration and that life-changing experience, I have been building the Mega Man collection that I could not afford back when I was a poor kid and I support Inafune-san on everything he does (you may or may not be aware: I'm a voluntary moderator on MN9's forums). I owe them.

Is there anything about Mega Man as a character that you’re drawn to?

More than the character, the gameplay!

Call me "simple-minded", but to me, simple things work better; and that's one of the many reasons why I always regard the original Mega Man series as the best one: while I acknowledge that other series have other more complex elements that enhance the gameplay experience, classic Mega Man has something that can never be matched: there is charm in its simplicity.

You mentioned that you’re “building the Mega Man collection [you] could not afford back when [you were a kid].” Can you tell me a little about this collection?

Well, the collection contains a few hundreds of items (mostly merchandising stuff like comics, mangas, toys, etc.)

Keeping up with what I have and what I don't has become such a complex task that I'm working on a website to document the whole thing so that I can have a quick reference before purchasing something that I most likely already have ^_^". The site is still years away from complete, but it's a lot of fun to work on.

This whole "collect them all" thing started kinda unintentionally, when, after getting my first professional job, I realized I could buy some of the many games I always wanted to have as a kid. Then I realized there were many other nice Mega Man related things that I was unaware of at the time and new merchandise that Capcom kept releasing...

I'm not sure exactly when it happened, but I eventually decided that I wanted a more proper, more complete and more coherent collection (at the time, all I had was a few items of this and a few others of that).

Here is an early picture of Jan 2011 when I was barely starting in this obsession with collecting mega man: https://goo.gl/photos/aM1h2JJ6L4FujugX7

And here are a few more recent pics, which does not include all items, and many of them are a bit outdated by now, but it's a good reference:

https://www.amazon.com/clouddrive/share/Y3fGPWpLSbGhkE4B3hN7ctPlSC7row82WFpC7sTltix?v=grid&ref_=cd_ph_share_link_copy

Are there any items in your collection that you’re particularly proud of or excited about?

This one:

https://www.amazon.com/clouddrive/share/mPvdYyKBZ3tRJRJBF2M02oiXuxb33PMJLcsle8yKTjk?v=grid&ref_=cd_ph_share_link_copy

The Mega Man face on the right was drawn by Keiji Inafune himself (the so-called "Father of Mega Man").

Best of all: this is NOT some overpriced stuff that I bought from a scalper on ebay. Inafune-san drew it for me, and for me only.

I’m intrigued by what you said about your background growing up. What is your home country, and would you say there’s anything unique about gaming culture there?

I was born in the north-west-ish part of Mexico. A region dominated by drug dealers, corruption and an antiquated old-world culture.

Back in the day, being a gamer was seen as a weird thing. We were the exception. Technology hadn't caught up there, so, those technology addicted geeks like me had a hard time trying to fit in. It wasn't so hard for me because I have always been an anti-social ^_^". So, all I had to do is keep being myself.

Thankfully, things have been improving over time. Specially with the advent of the internet, things have improved a lot. Mexico in general is now a big marketplace for AAA titles. So much that some big game studios like Microsoft now translate their games to "latin american spanish"; previously, all you would get was European Spanish, which, while perfectly understandable to any latin american, sounds a bit weird due to the marked European accent (imagine all your english subs and dubs being in British English).

Gaming has become so important in Mexico that, in fact, the roles have reversed: now it's harder to find someone who doesn't play any games than someone who does.

Something unique about gaming in Mexico: the video game making industry is almost completely non existent. For such a big market, one would expect everybody to be making games and trying to get a slice of the cake; but nope. We are happy to play games made by everybody else.

It’s so fascinating that you owe your computer programming career to Mega Man. When did you start coding, and did your early coding involve games?

I started coding at around age 14, when I got my first computer: an IBM PC 80383, with 1 Megabyte of RAM (yes, MEGAbyte, not Gigabyte) and a black and white monitor... Well, more like black and nuclear glowing green... aaah~, those were the days~

I would code in something called Quick Basic, a programming language that, if I recall correctly, was included with MS-DOS, the command line OS that was available on my computer.

And yes, most of my early works were very VERY VEEERY crappy text-only video games. Unfortunately, none of them survive to this day.

While my current job is not related to making games, I still take some of my free time to play around with available video game creation engines like Unreal 4, Unity 5 and so on. So much fun :)

I have a dream of making a more modern and story driven Mega Man game that remains truthful to it's old school NES roots... but that takes way more resources (especially time) than I have available... at least for now... Have not given up yet!

What games are you into today?

Today, I barely have any free time to play, but I'd have to admit I have a soft spot for construction games ^_^. I got very addicted to this game called "Project Highrise", although I think I'm almost cured of the addiction by now... I have also been playing Mega Man Zero on a live stream with a friend, as well as Dragon Ball Z Xenoverse sporadically.

I guess I can summarize my gaming preferences as follows:

1-Mega Man

2-Fighting games (mostly Capcom ones)

3-J-RPGs

4-Everything else. Not too much into AAA titles, but would give them a try if I have the chance.

Is there anything else about you that you think someone would need to know to truly understand your gaming history, and who you are as a gamer?

I'm a very shy guy!

Actually, I've always been a very anti-social, quiet, reserved, introverted person... but once I open up, you'd wish I had stayed that way ^_^"

One of our favorite Kickstarter traditions is the "gamer profile tier," in which one of our authors interviews a Kickstarter backer. Today, Alexa Ray Corriea (author of the forthcoming Kingdom Hearts 2) interviews Sam Grawe about his gaming history.

Sam Grawe is a 27-yr.-old programmer currently looking for a new location to settle down in. You can follow him on Twitter at @smgrawe.

Enjoy! - BFB

Alexa Ray Corriea: How did you get started playing video games? What is your earliest memory of playing one?

Sam Grawe: Oh boy, the earliest I can remember getting into games was when I was like 6 maybe? Probably earlier. My older brothers had an NES I loved to mess with, but I can remember anything specific from that. I liked messing with my older brother's Virtual Boy and remember getting in trouble for playing with a wire stripper and the virtual boy's cable to it's controller. I vividly remember always wanting to play with my friends' Nomad and or Game Boys while I was going to daycare. Tetris was awesome, but I never felt like I was good at it. The earliest memory I can identify as playing a game was a Sonic game on the Nomad and never being able to get past some crab/squid boss that had bouncing balls that you had to dodge to get pass. The stupid balls never bounced consistently.

I didn't have a system I could consistently play or use on my own until my parents got me a Game Boy Pocket. It was green! I was so cool. The first game that was mine and that remember playing on it was Pokemon Red because red was my favorite color at the time and dragons were (and still are!) cool.

Alexa: What were the first system and game you bought yourself and why?

Sam: The first game I bought on my own was Ratchet and Clank on the PS2 right around the time it came out. I was so hype for that game, I think I was like 12 or 13 at the time I got it. I don't remember how I learned about it, but I wanted it because it was Insomniac's first game for PS2 and I had loved and played that crap out of the first two Spyro games (Unfortunately I never did convince my parents to get me Spyro 3 before I got my PS2 and forgot all about PS1 games). I remember opening the game up on my way home and thinking it was so cool that the game manual was just a big ol' poster of the now iconic duo. I loved that game and will probably play every single Ratchet game that ever comes out because of my nostalgia for it.

The first console I bought on my own was a PS4 since it came out while I was an adult and had a real full time job, but I did manage to split the cost of my PS3 with my dad so both can technically qualify.

Alexa: What genre of games did you gravitate towards, and why?

Sam: I tend to gravitate toward character driven RPGs (JRPGs and the western RPGs that don't make me think about the numbers too much a la Mass Effect 2) and action/character action/action RPGs (KH series, Ys, Spyro/Ratchet, Assassin's Creed, etc).

Alexa: Is there any particular game or series that you played when you were young that had a significant impact on you? This can be your views on life, your views on yourself, your personal goals, fitness goals, career goals, etc. For example, I've been very open about my connection to Kingdom Hearts with my family, and how Lara Croft impacted my values.

Sam: Oh boy. This is the last question I've gotten to and I've been thinking about it ever since I've got your email. I've played a lot of games and it all sort of meshes together at some point. I contribute to our favorite manic pixie dream boy in KH, Sora, the fact that I try to act like it's generally a better idea to look try to look at something positively than it is to "give in to the darkness." Kingdom Hearts is also why I first dived into online forums since I first joined a forum to speculate with other fans about just what the hell might happen in KH2 (OH BOY were we in for a treat) especially as the KH: FM special ending and all of those things made their way over here. I tried my hand at writing for the first time on those boards. FFX is the game that cemented my love for JRPGs (while I liked VII and VIII they didn't quite make me feel like these were my favorite type of games). I still tear up a little when I watch Titus disintegrate into oblivion (or so I thought) while Yuna just doesn't want him to leave at the end of FFX. Persona 4 (or more accurately Giant Bomb's endurance run and then my personal P4:G playthroughs) let me know that video games can actually have fully realized characters in them, and that JRPGs didn't need to always feel like comfort food when I played them. Playing the Trails in the Sky duology is the closest I've ever come to finally trying to learn Japanese so I could play Kiseki games that haven't come out here, and that there are JRPGs whose story can actually stand tall when put up against my favorite books.

Alexa: Is there a particular character you identify with?

Sam: Not really? It's been an odd thing thinking about this since you'd think a semi-generic white dude who has played games for most of his life would have identified with a character in a game by now. I'm answering this question before I answer the "significant impact" question so I might elaborate on that there. So I'm going to pivot the question a little: "Is there a particular character you admire?" That I can answer a bit better.

I would say Estelle Bright from the Trails In the Sky duology is one of the character whom I admire most in video games, and is one of the primary reasons why Trail in the Sky is my favorite game of all time (I may have yelled at the Airship podcast a couple of times for never mentioning the Trails series). Estelle Bright is probably one of the only protagonists I have ever played as whose motivations for a decision I have never disagreed with in terms of how the position was presented and made. Most times in a video game story (especially in a JRPG) there will be times in the story where I want to slap a character and scream "YOU ARE BEING BLATANTLY STUPID AND NAIVE" or the entire reason I can discern for something to be happening is because the plot had demanded it or the game makers decided that there needed to be a bit of fan service (or whatever). That never really happens in Trails in the Sky, and if somebody does do something stupid they usually get slapped. She starts the game knowing who she is and who she want to be, and even though there are many opportunities for her to deviate from the path along her journey she never does. She's just so cool and I aspire to be as cool as her (in my own way). Characters like her make me excited for my little girls to start playing video games even though there are many many reasons for me to be terrified for them to even pick up a controller in the first place. Her characterization, and the characterization of most of the other characters in Trails in the Sky, made me feel like they were real people I could meet and would like to meet. I had only felt that happened before in Persona 4, my old most favorite game.

Alexa: Is there a particular console you favor? And does your choice have to do with usability or the catalog or the values of the platform?

Sam: At this point in my life I tend to just go where the games are. When I have a choice I tend to go Vita first due to portability and ease of use (I'm currently playing Trails of Cold Steel II on my imported P4: DaN Vita). It also makes it easier to pick up and play or put down so I can help out with two wonderful daughters. If my Vita is an option I'll probably be playing it on my PS4 since I don't have the time/money to build myself a proper PC yet. I used to be a PS fanboy, but I'm now more just nostalgic for the brand than I am a fanboy.

Alexa: Have you been to any conventions like PAX, E3, or PSX? Have you had any excellent fan moments at any of these with a creator or someone else in the industry you particularly admire?

Sam: I have only gone to a single day of PAX and that was back in 2013. I met Greg Kasavin and some of the Super Giant team after I played Transistor... and it crashed on me. I also poked by the Double Fine booth, but didn't exactly try to talk to anybody. To be honest I was kind of out of it the whole day since there were just so many people there, so even when I did talk to Greg I just thanked him for doing a great job with a game I was excited to play. After that I just sort of scooted away since I tend to be shy and get terrible anxiety when I think I might be wasting someone's time. My highlight of the whole thing was actually when I got to meet Vinny the day before when he commented on my Giant Bomb hoodie, but it was in passing since I think he was doing other stuff. It would be awesome to go again to PAX or some other gaming convention again some day, but at this point it's mostly been a problem of not having the time or the money to go do something like that. My favorite dev interaction these days has actually been following Keita Takahashi (@KeitaTakahash) on twitter since the man is a delight on that platform.

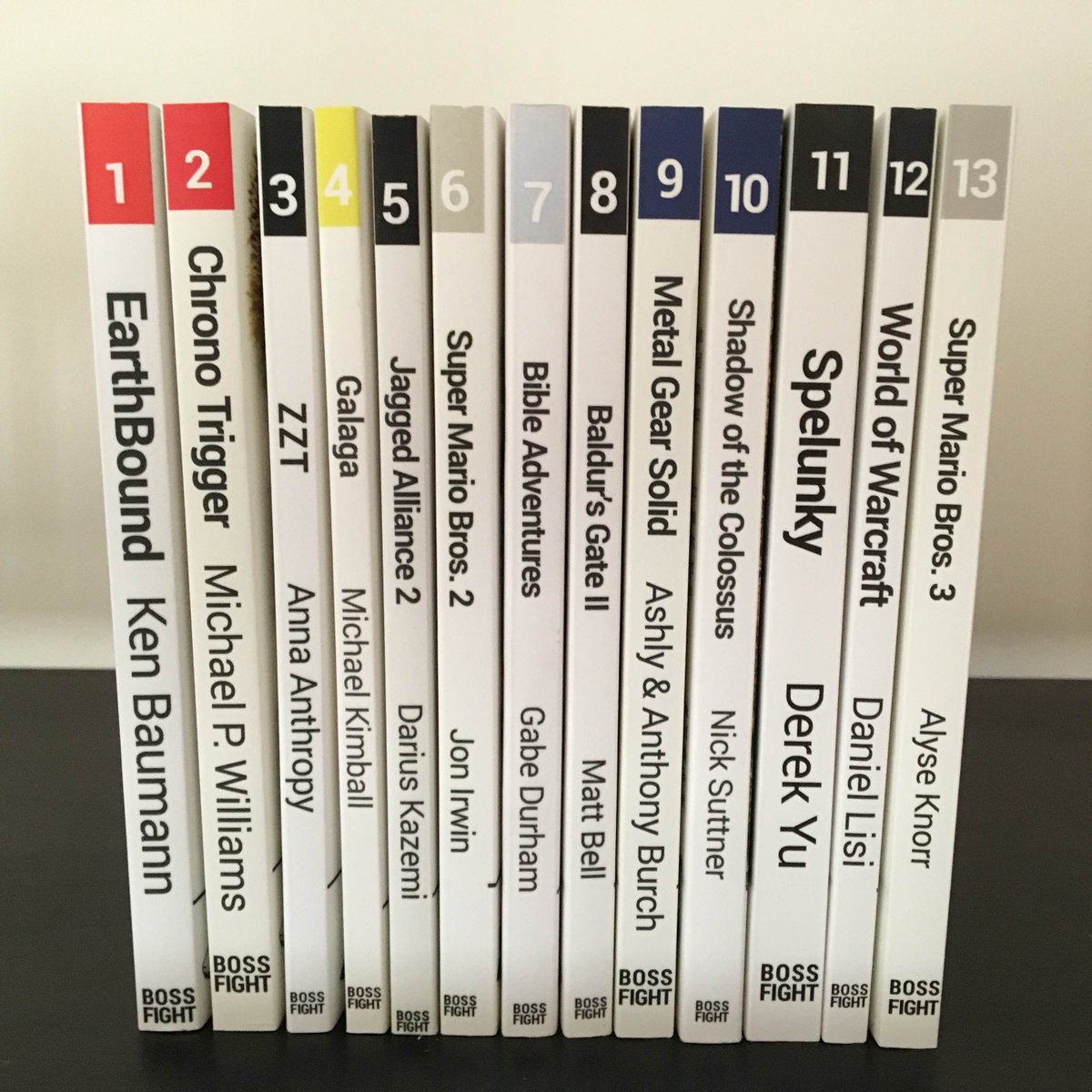

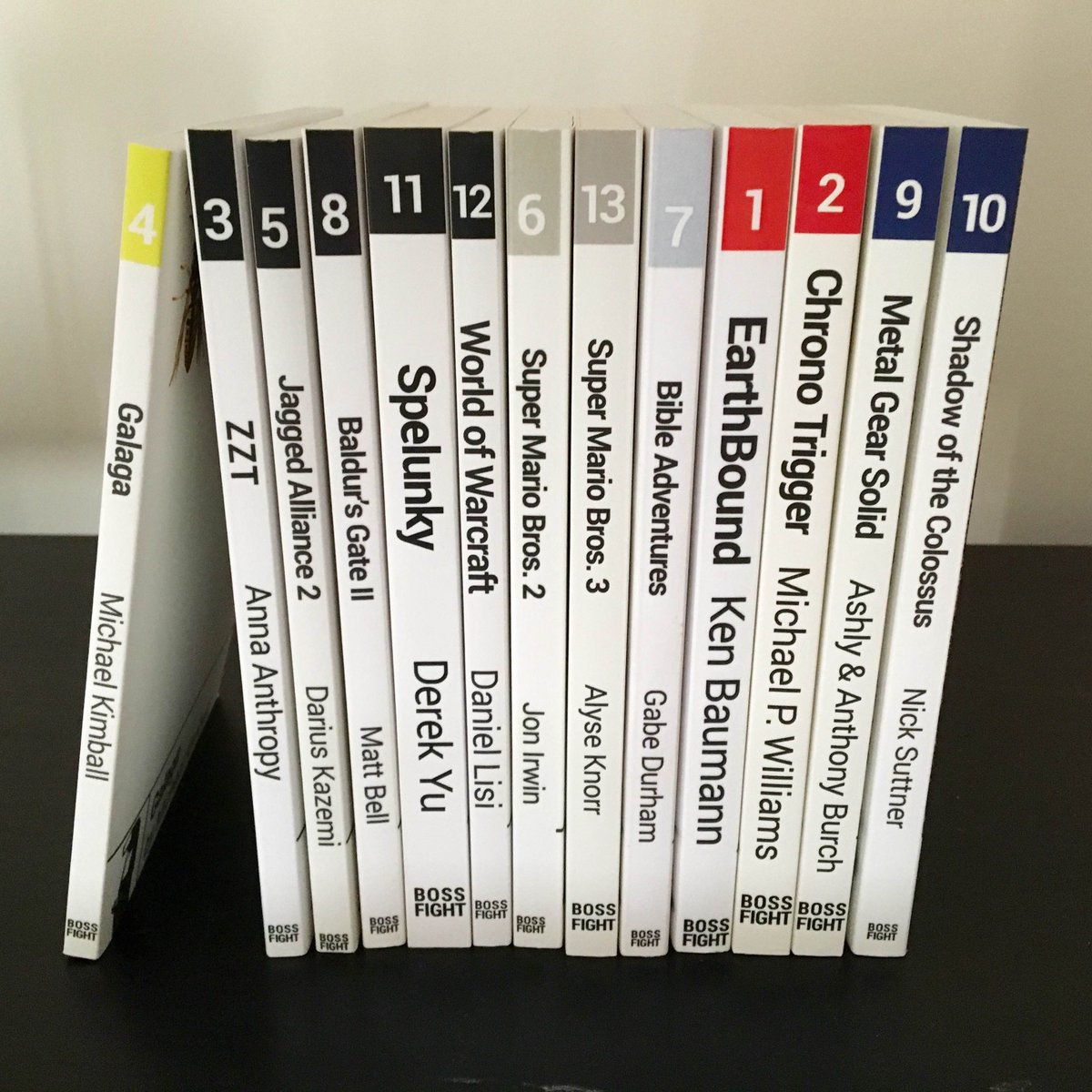

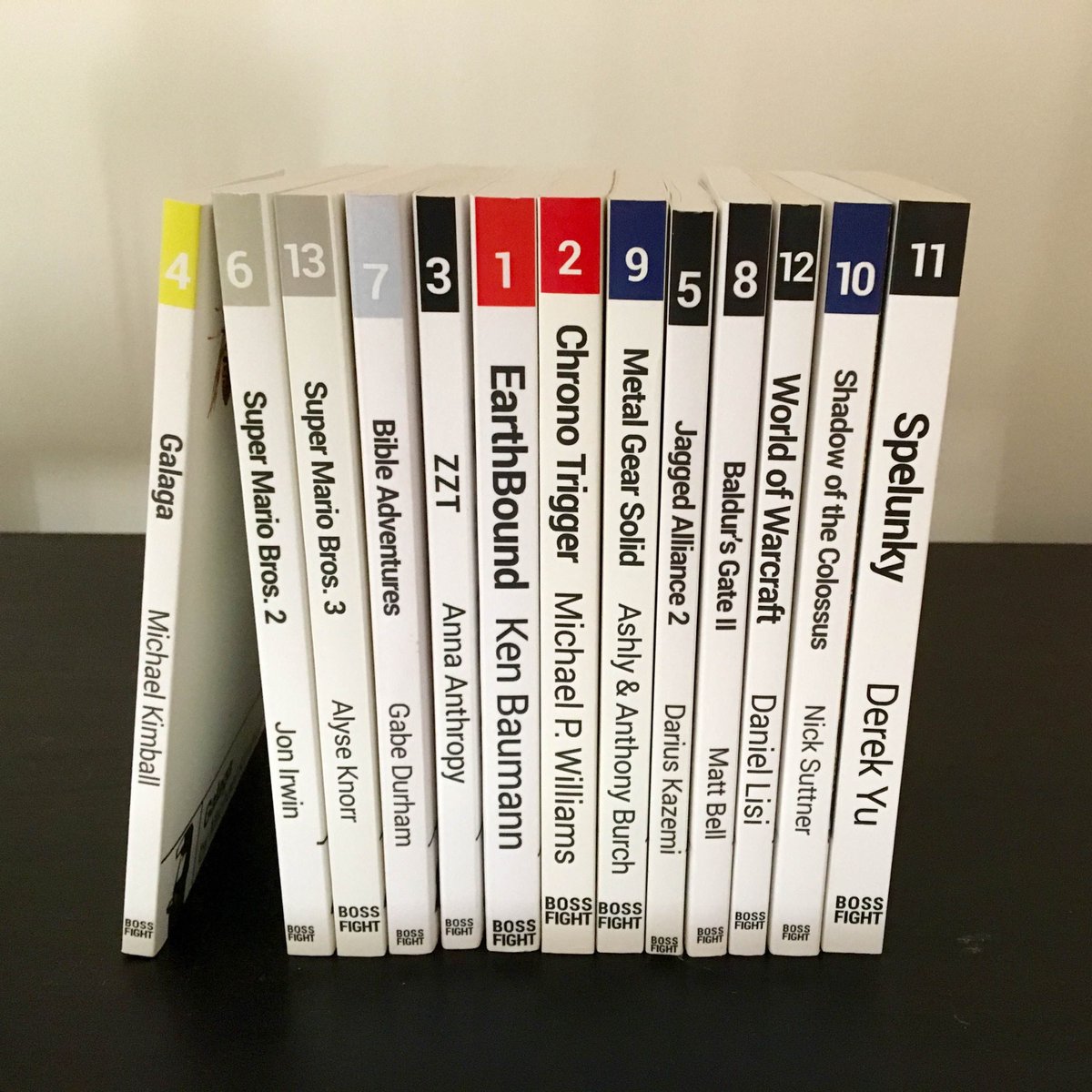

Arrange by Book Release Date

- EarthBound

- Chrono Trigger

- ZZT

- Galaga

- Jagged Alliance 2

- Super Mario Bros. 2

- Bible Adventures

- Baldur's Gate II

- Metal Gear Solid

- Shadow of the Colossus

- Spelunky

- World of Warcraft

- Super Mario Bros. 3

- Mega Man 3 (not out yet)

- Soft & Cuddly (not out yet)

- Kingdom Hearts II (not out yet)

- Katamari Damacy (not out yet)

Arrange by System

Arcade

PC

- Soft & Cuddly (not out yet)

- ZZT

- Jagged Alliance 2

- Baldur’s Gate II

- World of Warcraft

- Spelunky

NES

-

Super Mario Bros. 2

- Super Mario Bros. 3

- Bible Adventures

- Mega Man 3 (not out yet)

Super NES

- EarthBound

- Chrono Trigger

PS1 / PS2

- Metal Gear Solid

- Shadow of the Colossus

- Kingdom Hearts II

Arrange by Game's North American Release Date

1981

1987

- Soft & Cuddly (not out yet)

1988

1990

- Super Mario Bros. 3

- Bible Adventures

- Mega Man 3 (not out yet)

1991

1995

- EarthBound

- Chrono Trigger

1998

1999

2000

2004

- World of Warcraft

- Katamari Damacy (not out yet)

2005

2006

- Kingdom Hearts II (not out yet)

2008

We've got two live readings coming up! Both of them are planned around conferences (GDC and AWP) to maximize the number of you who can potentially make it:

1. Spelunky Release Party - San Francisco, CA - March 17 - 7:30 pm - Green Apple Books on the Park - Readings from Derek Yu, Nick Suttner, Anna Anthropy, and Gabe Durham

Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/174260796285720/

2. Heart-Pounding Panic - Los Angeles, CA - April 1 - 7:30pm - Stories Books and Cafe - Readings from Alyse Knorr, Matt Bell, Salvatore Pane, Jarrett Kobek, Nick Suttner, Daniel Lisi, and Gabe Durham

Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/562825637219672/

So if you're around, please join! See some readings, buy some books, get them signed, drink some drinks, meet some authors. It's going to be a couple of great nights.

Our next book, Shadow of the Colossus by Nick Suttner, comes out this holiday season. In honor of the 10th Anniversary of Shadow's North American release, please enjoy an early look at the book's introductory first chapter.

A massive, open world with almost nothing in it. A big-budget game that’s more interested in exploring the experience of its questions than distracting you with answers. An unwavering trust that players will figure out where to go, what to do, and even think about why they’re doing it. Shadow of the Colossus is a landmark in so many ways, and still unique more than a decade after its release.

It’s also a study in focus, as it was in its time amongst its peers. Resident Evil 4 released earlier that same year in 2005, revitalizing the entire survival-horror genre with a tight over-the-shoulder perspective that made combat a tense, precise nightmare. Just a couple of months later came God of War, a bold and bawdy exploration of Greek mythology with a deeply satisfying bloodlust.

All three games have since seen HD re-releases and are considered seminal events in gaming history. Yet both Resident Evil 4 and God of War hew closely to convention, very much gamers’ games filled with inventories, attack combos, and carefully scripted moments always upping the ante. Both games are also very filmic, with long expository cutscenes wrapped around every big event, and a monologue for every hero and villain that dives deeply into their lore.

Clearly, 2005 was an incredible year for games. But what interests me is just how far Shadow swung away from those other hits. Its reductions were across the board, and uncompromising: Only sixteen “enemies.” Only two weapons, both of which you start with and will never level up. You’ll never learn new moves, only strengthen your grip and your health over time. You won’t unlock new areas, only new challenges in places that have been accessible all along. You won’t meet any new main characters after the opening cinematic. There’s (almost) nothing to collect.

Yet despite all that isn’t there, Shadow is absolutely riveting. At a time when games were doubling down on the gamer by betting big on proven formulas, and leaning on the legacy of film to tell their stories, Shadow was content to spin its mystery up front and shove you into the blinding sun to fend for yourself and figure out the rest. The entirety of the experience lives deep within me, like some primordial dream. Soaring high above the sprawling desert, clinging to my foe as the wind laps at my unsteady feet. Finding the relief of fire at the bottom of a treacherous crevasse, itself in the shadow of an ancient, endless bridge.

*

I first read about Shadow in the pages of Electronic Gaming Monthly, a long-running gaming magazine I would later write for. A game in which entire levels were puzzles set atop the backs of massive creatures, the promise of an epic puzzle-platformer from the team behind the thoughtful, sweetly haunting Ico. Building on their craft and artistry, Team Ico’s Shadow promised action, and a gauntlet of giants to conquer. Its titular creatures were striking, even in those early screenshots. Towering, dimly sentient relics with piercing yellow eyes and mossy manes. I was smitten.

In broad strokes, Shadow is about a boy trying to save a girl. The situation is dire, and his last hope lies in a distant, long-abandoned corner of the world. He brings her to this place, throwing himself at the mercy of its overseer. This spirit tasks him with defeating a number of guardians that dwell within the land, and in exchange there may be a glimmer of hope for her yet.

But like so many wonderful moments in life and art, Shadow of the Colossus is defined by the space between its lines; the gulf between its quieter, contemplative moments and its tremendous spectacle. Strung end to end, its titanic battles would make for an amazing — if exhausting — barrage of action. But driving your horse across an imposing sun-baked expanse, twisting up through shade-mottled woods, only to find your ageless, unwitting foe at rest in the stillness of a lake gives the encounter exactly the breathing room it needs. Shadow lets its best moments come to you at your own pace, subtly leading and showing rather than telling.

*

There were rumors that Shadow was originally planned to have whole cities and dungeons dotting its spartan landscapes, lost in time to schedules, or budgets, or something equally mundane. And one of the best, most wonderful things about it is that it feels that way. The remnants of a world that once was, or never was, frozen in time. A lost civilization perpetually under construction.

There are so many empty, functionally useless corners of Shadow’s expansive world, but it hurts to even call them that. They always felt alive and mysterious, as if exploring the right nook or climbing an especially precarious peak would unlock…something. A bridge to that lost civilization, a seventeenth colossus, some armor for my horse maybe. Despite its creator Fumito Ueda telling me years ago in an e-mail interview that all of Shadow’s secrets had been found, it never felt that way, and still doesn’t.

Thankfully, the legacy and lessons of Shadow live on in gaming today, through a generation of fans, artists, and especially game developers whose work carries its influence forward. Game development has become democratized in recent years through cheaper and more user-friendly software while the audience has expanded tremendously through more ubiquitous platforms to play on. As a result, many players are looking for more varied games across the full spectrum of human experience, and some of the themes that Shadow explored — such as hope, regret, and sacrifice — have become both easier and more commercially viable to express. At the same time, series such as the Dark Souls games have built on Team Ico’s legacy, dropping players into vast, unforgiving worlds that seem to have existed long before they came along, with narratives that unfold through gameplay as much as through storytelling — no doubt influencing a future generation of developers to live by the tenets of trusting and respecting their players while giving them something surreal and spectacular.

*

Oh right, and I’m Nick Suttner, bearded indie game advocate. After writing about games for EGM and 1UP.com (where I hosted a retrospective podcast series on Shadow), I went to work at Sony to help shape the culture of independent games on PlayStation. Shadow is the entire reason I’m working in games, and specifically the reason I went to work at Sony (which published the game). I've spent almost nine years in the gaming industry championing the more artful, emotional, intellectually stimulating side of gaming, and truly, Shadow has been my constant muse.

My endeavor here as your guide, as a Shadow devotee, and as someone whose career and personal aesthetic has been so deeply influenced by the game, is to dig into the experience and unearth just what makes it so special. Why is Shadow still so singular over a decade later? How has it managed to maintain an air of mystery beyond that of any other game? I'm hoping that you've played Shadow already, but if you haven't made time for it I'm happy to give you an excuse. Consider this your companion guide — I’ll be playing through it again with a critical eye, talking about it with others who love it the way that I do, and sharing my findings along the way. To maybe even find that elusive quality that encapsulates the game's enduring appeal. Or maybe not, and to instead just get lost in the roar of the earth once again.

*

Pre-order Shadow of the Colossus by Nick Suttner here.

When I was a kid, I didn’t often have the luxury—much less the sense of spontaneity—to purchase video games without first doing my research. My monthly subscription to Nintendo Power was a great source of information, but the featured walkthroughs and “Pak Watch” previews were a poor substitute for actually playing Nintendo games. Luckily for me, my family didn’t live far from a video rental store. West Coast Video, a chain founded in my own city of Philadelphia, began stocking video games along with VHS tapes. I saw this video games section grow rapidly from a dedicated shelf to an entire rack, and finally to a complete section of the store. Eventually, West Coast Video and the recently moved-in Blockbuster became not only cheaper alternatives to buying games, but also libraries—places to find video games that had long stopped selling in stores. Unlike retail stores, where games were often locked inside towering plastic cases, video rental stores gave me full access to the packaging. Often enough, video games boxes were my first impression of games, and their imagery influenced the way I approached their contents.

In the late 1980s through the 1990s, the video game boxes that I mostly loved, sometimes hated, and often tried to imitate with pencil and paper, differed vastly from their counterparts in Japan. In some extreme cases, box art might be mutually unintelligible to players on opposite sides of the Pacific Ocean. With the help of the internet, it has become an easy task to make side by side comparisons of North American, Japanese, and occasionally European box art. Discussions about transoceanic box art differ- ences usually highlight the subjectively poor artistic merit of North American artwork compared against its Japanese predecessors, though defenders of the Western aesthetic are not in short supply. Box art comparisons, then, tend to become simple arguments over which region did it best, though recent matchups have also demonstrate subtle changes in the box art of American and Japanese versions, like how Nintendo’s beloved pink puffball Kirby tends to look angry and battle-ready on North American boxes, but seems to be having a jolly time on those same adventures in Japan. These slight variations, however, are nowhere near as noticeable as the radical splits in box art during the early days of console gaming. I began wondering just why box art localization has shifted away from highly idio- syncratic repackaging—why the inspired, sloppy, thrilling, ridiculous, or just plain baffling box art styles of yesteryear have mostly disappeared.

•

No one in my family seems to remember just when we bought an NES. I maintain that it was a present for my fifth birthday in 1987, though true to its original Japanese name, it soon became a “Family Computer.” My earliest memories of playing Nintendo were swapping controllers with my sister to play Super Mario Bros., cheering when my dad finally knocked out the celebrity final boss of Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!!, and attempting to make urban legend into reality by trying in vain to shoot down that mocking dog in Duck Hunt. None of these, however, can hold a candle to the events of April 3, 1988. That Easter Sunday, I awoke to a special kind of egg hunt that could only have been dreamed up by my mom. Golden (plastic) eggs had been scattered throughout the house, and I had to track each one down to unlock a hidden treasure. Inside the shiny eggs were all sorts of strange artifacts: an hors d’oeuvre skewer in the shape of a sword, a toy apatosaurus, a small metal key, a monster finger puppet. After I had assembled all of these items, I was given the ultimate prize, The Legend of Zelda.

I instinctively knew it would be special. The heraldic box art was already whispering to my imagination. The upper left of the regal escutcheon on the box was a win- dow to something shinier than any of the eggs I had found that Easter morning—the aureate cartridge itself. For me and countless other players, The Legend of Zelda was a golden ticket into the world of epic gaming. Japanese players, however, did not receive anything close to this spe- cial treatment. The box art of the original Famicom disk version, The Hyrule Fantasy: Zeruda no Densetsu, shows an anime-style Link crouched in front of the Hyrulian land- scape. The game itself was an elongated yellow floppy disk, a pale comparison to the shiny cartridge released in North America.

The box art conceived for other fantasy questing games in North America took cues from The Legend of Zelda’s packaging. Its own golden-carted sequel, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, shows a large jewel-hilted sword, and Square’s Final Fantasy took the typical role-playing imag- ery further, showing a crystal ball above a crossed sword and battle-axe. The Japanese Famicom boxes have vastly different imagery. Rinku no Bōken shows the elven hero slightly matured and adventuresome, and Fainaru Fanatajī depicts a fey swordsman in ceremonial armor in the now timeless style of series artist Yoshitaka Amano. Neither of these cartoonier approaches seems to have found favor with early marketers of Japanese games localized for North Americans. Instead of the heavy anime stylings of Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Quest series, for instance, the Dragon Warrior games feature scenes that could have been lifted from the covers of generic Western fantasy novels. These box art localizations exchanged cute for cool, childlike for adult, and play for adventure.

The larger adventure genre similarly translated approachable and ethereal Japanese box art into more intimidating and straightforward North American terms, sometimes with hilariously bad results. Perhaps the most infamous example of North American box art localizations is Mega Man. The character immortalized by this cover is far removed from the version on the Japanese release of Rokkuman (“Rockman”). Instead of a friendly robo-boy with an arm cannon who battled other bipedal robots, North Americans saw an adult in safety pads awkwardly wielding a pistol on a futuristic pinball landscape. Beyond the sheer incompatibility of this art with the game’s con- tent, the box art version of Mega Man is off-model, with strange bodily contortions and a misshapen helmet. His hangdog, almost haunted expression tells us what we can easily ascertain—there is nothing mega about this man.

Ultimately, North American NES players didn’t adapt the old adage about not judging a book by its cover— despite the fact that the gameplay of Mega Man had little to do with its packaging, the game sold poorly. But the North American manual for Mega Man tells a different story, and one closer to its Japanese origins. After skipping past the steroid-fueled welcome from Capcom’s partially eponymized mascot Captain Commando, the reader gets a glimpse at how Mega Man was envisioned for Japan— a plucky hero who is more playmate than action figure. Here in this 1987 package begins a long-standing tension between the Japanese Rockman and Western depictions of Mega Man.

(Read the rest of this essay in Continue? The Boss Fight Books Anthology.)

Today in our interview series Matt Bell (Baldur's Gate II) interviews Gabe Durham about Bible Adventures.

Matt Bell: It seems like as the editor and founder of Boss Fight Books, you might have a harder time than most writers choosing a game to revisit and write about. After all, you've seen a lot of pitches, and you've seen what works and what doesn't in other books in the series, and I'm sure you have a pretty good idea which kinds of games make the best choices. So why Bible Adventures?

Gabe Durham: I think that since I'm the guy steering this ship, one potential pitfall of writing a Boss Fight book would be feeling like I need to somehow write the ULTIMATE Boss Fight book--one that does it all. Picking this oddball subject immediately sidelines that sort of pressure.

That said, it IS a subject that lends itself to multiple approaches: a history of Color Dreams/Wisdom Tree, an analysis of each of the games, a reflection of my own experience with Bible Adventures and other Christian products, and a larger look at the legacy of these games.

Going into the project, my most useful guide for how to engage with a single work was Carl Wilson's Let's Talk About Love, about the Celine Dion album of the same name. Like Wilson, I liked the idea of looking hard at a cultural punching bag and investigating what the work can tell us about the world and ourselves. I became enamored with the question, "Why does Christian stuff like this exist at all? And what does that stuff have to do with religious faith?" So what looks at first like a winking history of a kitschy cult classic turns into an earnest look at the intersection of faith and commerce.

One of the odd things about Bible Adventures is that it's an unlicensed NES game. What does that mean, and what effect did that have on the game's development?

Nintendo of America had tremendous power in the NES era. If you were a third-party developer like Konami, you were Nintendo's bitch. Not only did they demand changes and censor content (no swears, blood, nudity, politics, religion, etc.), they also physically manufactured all the games and then sold them back to the developer at a high price per cartridge. This meant Nintendo decided when your game would be released, how many copies would be made, and how much they would promote it in Nintendo Power.

Wisdom Tree worked outside of this system. They were true indie developers (way before that was a term) who developed, manufactured, and sold their own games. The downside: They had to figure out where to sell the games, how to convince people that the games were legit, and how to get the game cartridges past the Nintendo's 10NES lockout system.

Bible Adventures stars Noah, David, and Moses's Mother. Last night, I watched the Darren Aronofsky film version of Noah's story, and was curious about how he'd turned it into a pretty decent action movie, among other things. To give us a taste of the gameplay in Bible Adventures, what's Noah's part of the game like?

It's a platformer where you pick up animals and bring them to the ark. Sometimes you've got to lure the animals with hay or knock them out cold to get them on board. The one really inspired game mechanic (referenced in the book's cover) is that you can stack multiple animals--so as Old Man Noah you can hoist horses and cows over your head and still run at a full clip back to the ark.

Unlike the other two games, which can be completed pretty quickly, "Noah" takes forever. It's fun for a little while and then most of us give up around stage 3. I've heard Afronsky's Noah is overly long too. I guess epic apocalyptic stories like the Noah myth lend themselves to overstaying their welcome.

For the purposes of the book, are you playing the game on an emulator or do you have an actual copy of the game? I once played it over a few beers at Salvatore Pane's house in Indianapolis, so I've had a very small taste of the real thing.

I played the real thing as a kid but this year it's been on a Sega Genesis emulator. (it's got slightly better graphics than the NES version.)

My own NES is packed away at my dad's place or I would have bought a copy of Bible Adventures on eBay by now. The game sold well in its day so it's not hard to find a cheap copy of Bible Adventures. Bible Buffet and Sunday Funday are another story.

The description of the book for the Kickstarter campaign mentions "our retro obsession with 'bad games.'" What do you mean by that? What are some of your favorite infamously bad games?

There's now a pantheon of famous bad games. Shaq Fu, Superman 64. The most famous bad game of all time is E.T. for Atari. And we all have memories of when we bought cheap games with high hopes and were sad to see them fail us. I remember buying a game called Hybrid Heaven for N64--I couldn't believe how awful it was and that I was stuck with my poor choice.

In the book, I get into the fact that retro games collecting has created a weirdly inverted retro games market: Classics like the Mario games can be bought for cheap, but Bonk's Adventure for the NES goes for a lot of money now because nobody wanted it when it came out. Same goes for several Wisdom Tree games. This phenomenon partially explains the recent rerelease of Wisdom Tree's lone SNES game, Super 3D Noah's Ark--it offers collectors a new shot at checking an item off their list.

As the editor of Boss Fight Books, what's the game you're most surprised you haven't received a pitch for yet? Is there something that seems obviously to deserve this kind of treatment but hasn't been suggested yet?

Star Fox. Starcraft. Mario Paint. Wild Arms. Bust-a-Move. That drug dealer game for TI-83. I also haven't seen a pitch for League of Legends, the most popular game in the world.

To me, it's all about the author's take, though. Any game could make a great book or an awful one. Finding out what happens when we devote all this attention to a single cultural artifact is the big experiment and the big reward, so I'm trying to not get too hung up on HAVING to do books on certain games but instead finding the right game/author combos that will open the series up in exciting directions.

Today in our interview series, Chrono Trigger author Michael P. Williams asks Matt Bell some questions about D&D and his forthcoming book, Baldur's Gate II.

Michael P. Williams: I've got to tell you up front: I'm a Dungeons & Dragons nerd who has never roleplayed in real life, but I read almost every Dragonlance novel published through the mid-1990s, and I adored the “Monstrous Compendia” published by TSR. What has your history with D&D and roleplaying games in general been like?

Matt Bell: My D&D history begins with the computer games, not the pen and paper game, although the timing of getting into both modes was pretty close. As far as I can remember, the first D&D experience I had was SSI's extraordinarily difficult Heroes of the Lance, adapted from Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman's Dragons of Autumn Twilight, which I didn't read until years later. Shortly after, I found my dad's copies of the Basic and Expert box sets hidden high in a closet in our spare room, which introduced my brother and I to the original game. In the following years, we played nearly every D&D game that came out for the PC, and we bought and read and planned from many of the second edition AD&D rule books and campaign settings. Despite how much time and money we invested in the game materials, I don't think we actually played very often, or at least not until we were much older. (My brothers still play, and when I was writing The Last Garrison I rejoined them, but by then we were playing fourth edition.) At the time, we just couldn't find enough other people to play with, and it's very hard to play a two-person game. I think that was one of the alluring aspects to most video game versions of D&D: They simulate what is essentially a social experience, translating it for a single player.

As a novelist and an RPGer, you've had the power to create characters in a variety of settings. What similarities and differences have you experienced with creating characters for novels, for customizable computer RPGs, and for tabletop RPGs?

One of the things I talk about in the book is about how Gorion's Ward, the protagonist of the Baldur's Gate saga, is presented to the player in a very similar way to how fairy tale characters are constructed. Rather than the kind of fleshed-out round characters we're used to in most novels, where characters come with explicit full psychological motivations and backstories and so on, Gorion's Ward is given very few traits when the story opens, just a sketch of a past and a handful of starting statistics and skills that do not by themselves create character. Instead, the player is tasked with interpreting these mechanical aspects of the game into a person they can invest in emotionally, which occurs through character choices in response to the puzzles and story decisions of the game, and through character customization when you gain new levels or equipment. In a novel, you're usually given quite a bit more about the character, and of course you don't usually get to chart the course of the action. But in my own work, it's still important to leave some blanks in the character's makeup that the reader will have to fill themselves. That's part of what allows a reader to become invested in the character and his or her story, this sense that they're the ones who actually created the character, by imaginatively investing so much of themselves.

Your book is centered around Baldur's Gate II, a game that is a sequel to Baldur's Gate, and with its expansion pack Throne of Bhaal considered, is also a sequel to itself. What makes this a standout game compared to other video games in the larger Baldur's Gate series?

I think Baldur's Gate II is the heart of the series. The first Baldur's Gate was a revolutionary advance in D&D gaming, but its story is much thinner than BG2's. Because it deals with lower level characters, the gameplay in BG1 isn't nearly as difficult or as interesting, and it also has a more generic fantasy art style than BG2. As for Throne of Bhaal, it's a great expansion—really almost a true sequel—but it's so reliant on an understanding of Baldur's Gate II that it would have been hard to write about on its own. Despite being the middle of what is essentially a trilogy of games, Baldur's Gate II is probably the best vantage point from which to discuss the whole.

Baldur's Gate II is set within the context of the D&D campaign setting, Forgotten Realms, while your own D&D novel, The Last Garrison, is not set within any particular campaign. How important is the Forgotten Realms brand name to Baldur's Gate II? How might the game look if it were set in another D&D campaign, like highly polytheistic Dragonlance universe, or the very gothic Ravenloft setting?

It's an interesting question, because Baldur's Gate II is set in a part of the Forgotten Realms I hadn't read much about at the time, in the setting's novels or rule books. I think that was probably by design, as Bioware has made a similar smart decision with other licensed worlds, like not setting their Star Wars RPGs in the same time period as the movies. BG2 definitely has the Forgotten Realms in its DNA, and your quest takes you to some of the most famous places in that world, like a drow city in the Underdark, which must have pleased fans. At the same time, I think the designers had a lot of room to make their corner of the Forgotten Realms their own, for the purposes of the game. The other games built on the Infinity Engine that powers Baldur's Gate are probably more tied to their respective settings: The Icewind Dale games are set in the titular location, made famous by R.A. Salvatore's bestselling Drizzt Do'Urden series of novels, and Planescape: Torment—maybe my favorite of these games, despite writing about BG2—is absolutely integrated into its campaign setting, and probably couldn't exist without it.

So far, Boss Fight Books has tackled three very different RPGs: Earthbound, a Japanese RPG set in a modern world; Chrono Trigger, another JRPG set in a fantasy world; and finally Jagged Alliance 2, a Western RPG set in modern times. Baldur's Gate II, a fantasy WRPG, completes this matrix. What similarities and differences do you see among Baldur's Gate II and these other games? Also, how will BG2 the book differ from these previous Boss Fight installments?

To be honest, I haven't played more than an hour or so of both Earthbound and Chrono Trigger, so I can't speak to them too much. My instinct is to say that Baldur's Gate II is less whimsical than those games, but BG2 has its moments of whimsy and humor too, and I know both Earthbound and Chrono Trigger are very serious in their own ways. I do think Jagged Alliance 2 and Baldur's Gate II share a lot in the ways that players interact and come to care for their characters, as that was the most memorable part of Jagged Alliance 2 for me. As for how my book will differ from the earlier books: I'm sure there's some crossover, but one unique thing I'm trying to do is to explicitly explore how different game systems work from a novelist's perspective. For instance, Baldur's Gate II is such a story-driven game, but how do narratives work to create tension and conflict when the character isn't bound to follow any particular storyline at any time? Or how does character development work, compared to how it works in a novel? There will also be critical discussions of the game's depictions of violence and morality and romance and gender, subjects I don't think have been covered in the same way in earlier books. It's an incredibly rich game, and its ambition means there's a lot of material to explore.

I'd like to say I'm chaotic neutral, but I'm probably just a boring ol' neutral good. What is your favorite of the nine D&D alignments, and where do you think you'd fit into this scheme?

In pen-and-paper D&D, I pretty solidly played chaotic good characters, which seems about where I'd categorize myself in real life, although I probably lean more lawful these days too. In novels, I like a character who's willing to bend the rules for the greater good, and in my own writing I perhaps especially like characters whose belief in their own goodness compromises them morally, by allowing them to take actions that without that self-justification would be clearly wrong. I think most otherwise good people compromise themselves morally in many small ways, and I'm always interested in the stories we tell ourselves to get away with those compromises. That seems like the province of the chaotic good, and it's probably one of the more interesting spaces in D&D's alignment system.