This is the fourth in our author-vs.-author Boss Fight Q&A series. Both Sebastian's book on Final Fantasy VI and Gabe's book on Majora's Mask are funding now on Kickstarter.

This is the fourth in our author-vs.-author Boss Fight Q&A series. Both Sebastian's book on Final Fantasy VI and Gabe's book on Majora's Mask are funding now on Kickstarter.

It feels impossible not to compare Majora's Mask with its older sibling — like it's the Solange to Ocarina of Time's Beyoncé. How does/doesn't it stand on its own, and how does/doesn't it fit into the Zelda canon? Do you even think OoT is even the right reference point, or is there a better game to set beside Majora's Mask as a point of comparison?

I think Ocarina is totally a natural reference point. Majora was built from the parts of Ocarina by many of the same people who made Ocarina. Those developers were thinking about Ocarina constantly because they assumed that most of Majora's players had already played Ocarina, and so they worked hard to differentiate Majora from Ocarina, to deliver a novel experience. I like the Beyonce/Solance comparison -- that tracks for me, especially for how Solange seems to ask of her music, "What is my blockbuster sister NOT doing?"

Link's Awakening is another useful reference: It's the game that first showed that Link can leave Hyrule, Zelda, and Ganon behind -- AND that Link's adventure can contain surreal or mysterious elements -- and we'll all still accept it as a Zelda game. (And in both games, those elements largely came from Yoshiaki Koizumi.)

Last, there's the German movie Run Lola Run, which the part of my book that was

excerpted in Polygon brings up. According to different developer interviews, Lola either partially inspired Majora or their similarities are pure coincidence, but either way you can see a bit of Majora in the movie's "hero must replay the scenario until she gets it right" plot. Groundhog's Day gets brought up too, but that movie is more ponderous and less goal-oriented than Lola or Majora -- even if

[90s movie SPOILER] it's love that saves him in the end.

The concept of time is at the heart of both N64 Zelda entries, but in very different ways. How else do the games speak to each other?

Ocarina set up Majora really well for how it would play with time. Ocarina already had an in-game clock that switched from day to night, though it only ran in certain locations. And Ocarina already featured an ocarina with the power of time travel. These elements were a boon for a time-strapped development team trying to make a sequel quickly, and they pushed both the in-game clock and time travel much further in Majora.

This is similar to the use of masks. The masks in Ocarina make for a fun quest, but they aren't a huge part of the game. Majora asks, "What if the masks change how everybody treats you?" And, a step further: "What if the masks change YOU? Your body, your size, and your abilities." I don't think the mask mechanic at the core of Majora would exist if there hadn't been some light use of masks in Ocarina.

It was by no means a flop, but why do you think Majora's Mask didn't have the same runaway success of its older sibling? What do you think might have happened if Majora's Mask had been released before Ocarina of Time?

I've thought about this a lot, and here are a few factors that hurt Majora's sales:

- It's a late-gen N64 game. If you look at the list of the top-selling N64 games, they all came out before Majora. And Majora has the dubious honor of "bestselling N64 game released after 1999."

- It famously arrived on the same day as the PS2, the console with the greatest slate of launch titles in history, and got a little lost in the shuffle.

- Its sales were hurt by the requirement of a RAM upgrade called the Expansion Pak -- which everyone who didn't own Donkey Kong 64 had to buy separately. There were reports of stores that had Majora copies but had run out of Expansion Paks.

A "Majora comes out first" timeline is fun to consider. It definitely would have sold better, but it also would have confused a lot of players because many of its design choices skewed away from over-tutorializing in the early game. The devs envisioned a slightly older player who has already played Ocarina.

It would also be weird to start with a bold experiment in a new land and then return with a relatively safe hero's quest in Hyrule. Majora places itself in the tradition of "we gave you exactly what you wanted the first time -- now here's a darker sequel." Like Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey. Or Babe: A Pig in the City. A lot of people, myself included, are hoping they go in a Majora direction for the BotW sequel. Mostly I think we mean: We hope they use this as an opportunity to surprise us. They gave us the big classic Zelda adventure: Now what else do they have to show us?

Majora's Mask's initial Japanese release date was less than 18 months after Ocarina of Time. What the hell was Nintendo thinking, and how the hell did the development team do it? How did they manage to make something so idiosyncratic—and so right—with so little time and with recycled resources?

Majora's developers were masters of reusing assets. There is a chapter in the book titled "The Art of the Remix" because they did such an incredible job of recontextualizing characters, enemies, items, and music from Ocarina and making it feel... not just fresh but often eerie, turning Termina and its inhabitants into a sort of Bizarro Hyrule. The developers turned the similarities into a strength.

Also, there were not a lot of team meetings. The devs just divvied up the workload and got to work. For instance, Koizumi was more in charge of Clock Town, the game's central hub, whereas Eiji Aonuma was more in charge of the rest of Termina and the dungeons. Composer Koji Kondo got almost no notes and was left to do his thing. Mitsuhiro Takano wrote the dialogue. And we're lucky that a lot of elements worked well on the first try because the team truly didn't have time to go back and change things.

The last answer is kind of a downer: Nintendo was not immune to crunch culture, though nobody called it that yet. I think the team worked too hard. Poor Takano, newly married, didn't see his wife enough and had to wait to take his honeymoon until after the game was done.

Majora's Mask is dark, with constant reminders of the passage of time, mortality, and existential futility. It feels less straightforward—it's no save-the-princess story—and far more cerebral and somber than any previous Zelda game (and most/all of the ones that came after it). How does the game manage this and find some sense of balance and appeal? What does joy look like for the player within the game, and for the people of Termina?

The game does a great job of balancing that somber tone you mention with a lot of classic adventuring.

For the player, I think there's a lot of joy in helping people. The characters in this game feel much more well-rounded than your typical NPC -- perhaps because you catch them in so many different situations and moods throughout each of the three days. They feel antonymous, and you get to know them slowly.

I will say, though, that for me Majora is the most stressful Zelda game to play because of the ticking clock. I'm so scared of screwing something up and having to start all over again! Majora is by far my favorite Zelda game to think about and talk about, but my favorite Zelda games to relax and play for fun are Breath of the Wild and A Link to the Past.

I have been thinking endlessly about Siobhan Thompson's recent tweet: "There are currently three types of video game: 1) you are a special fighting shootboy who shoots things 2) oh I get it, it's a metaphor for depression 3) nintendo." Joke aside, it feels like there is a kernel of truth there, and Majora's Mask seems to fit somewhere between #2 and #3. Do you think the game reflects on depression/mental illness? If so, how? Do you think this was the first major Depression Game?

Interesting! I guess it doesn't feel to me like a game about mental illness so much as it is a game about people dealing in different ways with the approach of death.

To feel despondent in the wake of an impending apocalypse makes a lot of sense. To me, the least mentally healthy characters in the game are those who refuse to believe what's going on, though they find their way to acceptance eventually.

I think Majora's Mask works nicely as a metaphor for any worldwide disaster: climate change, our current life dealing with COVID-19, or nuclear war. Majora's developers tell the story of being at a colleague's wedding at the same time that a North Korean rocket flew over Japan. It turned out the rocket was a failed attempt to launch a satellite into orbit, but all of Japan wondered if this was a declaration of war. The contrast of the rocket and the wedding informed the game: How weird it is to try to live a normal life with such a grave threat going on in the background. This is explored most literally in Majora in the Anju and Kafei wedding plot.

But to cycle back to that tweet: I think one thing that's really cool about Majora is that it chews on all this heavy stuff, but it is still unapologetically thing #3: Nintendo. Majora may be dark, but it's also silly, sweet, and playful -- and that duality serves it so much better than if it were merely a Serious Art Game. Especially in the year 2000, a time when most game studios were obsessed with nailing the aesthetic of action movies. Majora's devs had their pick of two different Link designs from Ocarina, and could have easily have made Majora starring adult Link. The fact that they chose Kid Link instead says a lot about the kind of game they wanted to make.

One of our favorite Kickstarter traditions is the "gamer profile tier," in which one of our authors interviews a Kickstarter backer. Today, Gabe Durham (Boss Fight's editor and author of Bible Adventures) interviews Daniel Greenberg about his gaming history.

Gabe and Daniel did the interview in person from the Portland Retro Gaming Expo. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity by Michael P. Williams. Enjoy! - BFB

Gabe Durham: What got you into video games?

Daniel Greenberg: When the NES has its worldwide launch in 1986, we couldn't get one for a while. It was kind of a novelty... My brother, who is about eight years older than me, had a Commodore 64, which my was father could afford at the time. When I was old enough to be able to crawl up into the seat and mess with it and play with it, I think I was playing Test Drive and Kickman and whatever else I could get to boot. We also an old Atari 2600, and this was when you could get the games for literally nothing: KB Toys had bins that were like three for a dollar.

G: So you benefited from the Atari Crash.

D: Oh yeah. And by the time we could afford an NES in 1988, there was plenty out to pick and choose from. We ended up getting some great games by sheer luck. With those covers, there was no way of knowing what you’d get! Games like Bubble Bobble, Mario, Zelda, Marble Madness—

G: Oh, that was a big one for you?

D: That was the only game I could get my father to play. He held the controller upside down. I have no idea why he did that to this day.

G: What do you think made you stick with gaming over time?

D: Probably the shared memories. I remember playing the first Final Fantasy with cousins, one of whom has since passed away. We’d all huddle around the TV at my grandmother’s house and play Final Fantasy or Championship Bowling. A lot of people remember running around outside and playing with friends as popular characters like Ninja Turtles, but for us it was video game characters. It was just so familiar to us. So when I moved away, which was not quite in the age of online gaming, we were able to stay connected by talking about the games were were playing on the Nintendo and Super Nintendo.

G: How has your taste in games changed over time?

D: Part of it is my ability to play them. When I was young, for example, I loved the music in Ninja Gaiden, but little me never had the skill to get far enough in that game to actually enjoy it. Whereas Bubble Bobble’s music was a 40-second loop, and we could get all the way through that, so that's burned into my head forever.

G: Oh man, that song!

D: As you get older, you get into longer-form stuff like strategy games and RPG. I got into Civilization when I was at an age to be able to crunch the math and appreciate what was going on behind the scenes. Civilization for the PC wouldn't have appealed to me, with the traditional war-gamer and utilitarian user interface, but the polished-up version with the mouse interface for the SNES made it really accessible.

G: How has your career intersected with games?

D: When I got older, and was interested in computer programming—and I’ve programmed for a number of different companies—I always appreciated the code and complexity that goes into game design. My second undergraduate degree at George Mason University was in computer science, and I’d see students working late at night on game projects in the labs. As I’d help them debug their work, it occured to me very quickly that the projects they were assigned were way more fun than my own assignments! I pivoted over to a degree in applied computer science in game design degree, and followed through to a master’s, and then into teaching as an adjunct professor of game design at George Mason, teaching game history and game design, and working closely with first- and second-year students to make sure they know the fundamentals and work from a common lexicon.

G: How do you put together your syllabi when there are so many resources out there? What are the fundamentals?

D: You can lost in game history, so you need to look for the touchstones. One of my favorite books is Tristan Donovan’s Replay, which takes a slow, segmented approach from the Festival of Britain in 1951 all the way to the end of the 20th century, offering a controlled window into some key events. And his storytelling really makes it work: I don’t care for games textbooks that read like social studies texts, listing just facts and figures. I find it doesn’t engage college-age students and it doesn’t stick with them either.

G: Is a lot of the study of games also the simultaneous study of games history? Learning how to do it by how people did it?

D: My students typically take the two classes "History of Computer Game Design" and "Basic Game Design" concurrently. “Basic Game Design” is about understanding the shared language and common patterns, and since this is usually their first time designing games, we focus on simple 2D experiences in GameMaker or Construct and help them get a few games under their belt. One thing we absolutely must have them do is develop a portfolio by the time they finish the program. We encourage them to go to game jams like Ludum Dare or Global Game Jam and work in the student programs like the Game Analysis and Design Interest Group we have at George Mason. In a few weeks, we’re going to be doing a 24-hour livestream to benefit Extra Life, but in addition to playing games, they'll also be making games for the stream.

G: So then they’ll watch the streamers play the games that they just made.

D: That’s the hope, yeah!

G: Is that one of the most satisfying things for your students, when they've completed a game and can watch someone else enjoy a game they had made?

D: When they’ve finished their first midterm, and they’ve finished their first thing—it’s not really a complete game, but they’ve seen that they can do it. And that's huge. The inertia of getting there is a big problem. When they first come into the program, you ask, “Who has an idea here for a game?” And everyone will raise their hand. Everyone comes in with their golden baby, and we have to give them two options. Either try to make it while understanding where you are in your skill development, or take the “James Cameron route”: Wrap up that game, set it aside, and work on other stuff until you feel like you’re ready for it.

G: Oh, the old Avatar treatment!

D: Exactly. He’s said how he wrote that in high school. “Unobtanium,” right? I believe him when he says he wrote it in high school! So if something is precious enough to you, and you don't want to damage it with amateur efforts, you’ll work on other things until you get to the point that you can make it.

G: Are you working on any of your own projects?

D: A few! I’ve been a writer for a few years. I’m currently working on Pat Contri’s Super Nintendo book with a group of other writers. I’m also part of a group called Winterion Game Studios currently based in Maryland. It's sort of a creative clearinghouse for me and my friends. I had bought all of this video equipment when I was a graduate student, and my friends and I decided to use it to make let’s plays, which we’ve been making for about three years now, focusing on older titles. It gives us a chance to do post-hoc analysis where we sit down and experience the game as accurately as it was intended. There’s something to be said for taking a single work, breaking it open, and getting some context for it. That’s why I wanted to back Boss Fight Books for Season 4. I hadn't even realized it existed until then! I appreciate the format and the concept: deep-diving into games, getting out and interviewing people. Those are time-limited things: There are amazing anecdotes from people in this industry, and we’re not going to have the opportunity to talk to them in 50 years, 100 years. The people and events behind the games, the context, the development, the marketing, what's going on in the world at the time, all form interesting and crucial stories.

G: Absolutely. I think many people have started realizing this as people in the industry have started to retire, or get older.

D: We just had Nolan Bushnell spend some time with us at George Mason as a game pioneer in residence. He was able to explain his time at Atari in the 1970s to our students, and that was invaluable. The students have read the history in books, but to hear it from the source was so good for them.

G: Speaking of books, tell me a bit more about your work on Pat Contri’s SNES book.

D: We had the stack of over 700 games made for the system to write for. No one is champing at the bit to review Dirt Racer or Bébé's Kids or some other dreaded games, so we just split the games up as made sense. I had a good set-up for Super Scope games, so I tackled a lot of those. You also don’t want to give somebody twenty RPGs, because some games are going to be longer to digest.

G: How does Super Scope hold up these days?

D: Surprisingly well! The device’s accuracy is pretty good, so as long as you’ve got a good receiver and a light gun. We’ve also got a nice Sony Trinitron TV that we’ll play on. But for the games themselves, there’s not a whole lot there. A few are fun, but by and large it was a novelty. A lot of rail shooters.

G: What in gaming tends to excite you the most?

D: I’m always compelled by what my students, present and former, are doing. We have a program called the Virginia Serious Game Institute, where we given students some office space and the time to work on their ideas. Some of the people I’ve worked with are doing UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) flight simulators, and others had a great simulation program for training firefighters: It’s a lot cheaper to practice 100 times in a simulator than set a real building on fire and then rebuild it! We’ve also had a program for the State Department for diplomats to simulate emergencies in VR renditions of embassies. It can be invaluable training.

G: Is there anything else we should know about you?

D: Gaming helped me meet the love of my life! When I founded Winterion, I started getting into discussions on Twitter about older games, and suddenly Alex and I are talking back and forth about The Legend of Kyrandia, a lesser-known point-and-click adventure series from Westwood. She knew it, I knew it, and before I knew it, a few months later we’re going to see Madame Butterfly together at the Kennedy Center. And now it's been a wonderful year-and-a-half together and counting!

*

Check out Daniel's projects below!

https://youtube.com/winteriongamestudios

https://twitter.com/winterion

https://winterion.com

We've got two live readings coming up! Both of them are planned around conferences (GDC and AWP) to maximize the number of you who can potentially make it:

1. Spelunky Release Party - San Francisco, CA - March 17 - 7:30 pm - Green Apple Books on the Park - Readings from Derek Yu, Nick Suttner, Anna Anthropy, and Gabe Durham

Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/174260796285720/

2. Heart-Pounding Panic - Los Angeles, CA - April 1 - 7:30pm - Stories Books and Cafe - Readings from Alyse Knorr, Matt Bell, Salvatore Pane, Jarrett Kobek, Nick Suttner, Daniel Lisi, and Gabe Durham

Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/562825637219672/

So if you're around, please join! See some readings, buy some books, get them signed, drink some drinks, meet some authors. It's going to be a couple of great nights.

Today in our interview series Matt Bell (Baldur's Gate II) interviews Gabe Durham about Bible Adventures.

Matt Bell: It seems like as the editor and founder of Boss Fight Books, you might have a harder time than most writers choosing a game to revisit and write about. After all, you've seen a lot of pitches, and you've seen what works and what doesn't in other books in the series, and I'm sure you have a pretty good idea which kinds of games make the best choices. So why Bible Adventures?

Gabe Durham: I think that since I'm the guy steering this ship, one potential pitfall of writing a Boss Fight book would be feeling like I need to somehow write the ULTIMATE Boss Fight book--one that does it all. Picking this oddball subject immediately sidelines that sort of pressure.

That said, it IS a subject that lends itself to multiple approaches: a history of Color Dreams/Wisdom Tree, an analysis of each of the games, a reflection of my own experience with Bible Adventures and other Christian products, and a larger look at the legacy of these games.

Going into the project, my most useful guide for how to engage with a single work was Carl Wilson's Let's Talk About Love, about the Celine Dion album of the same name. Like Wilson, I liked the idea of looking hard at a cultural punching bag and investigating what the work can tell us about the world and ourselves. I became enamored with the question, "Why does Christian stuff like this exist at all? And what does that stuff have to do with religious faith?" So what looks at first like a winking history of a kitschy cult classic turns into an earnest look at the intersection of faith and commerce.

One of the odd things about Bible Adventures is that it's an unlicensed NES game. What does that mean, and what effect did that have on the game's development?

Nintendo of America had tremendous power in the NES era. If you were a third-party developer like Konami, you were Nintendo's bitch. Not only did they demand changes and censor content (no swears, blood, nudity, politics, religion, etc.), they also physically manufactured all the games and then sold them back to the developer at a high price per cartridge. This meant Nintendo decided when your game would be released, how many copies would be made, and how much they would promote it in Nintendo Power.

Wisdom Tree worked outside of this system. They were true indie developers (way before that was a term) who developed, manufactured, and sold their own games. The downside: They had to figure out where to sell the games, how to convince people that the games were legit, and how to get the game cartridges past the Nintendo's 10NES lockout system.

Bible Adventures stars Noah, David, and Moses's Mother. Last night, I watched the Darren Aronofsky film version of Noah's story, and was curious about how he'd turned it into a pretty decent action movie, among other things. To give us a taste of the gameplay in Bible Adventures, what's Noah's part of the game like?

It's a platformer where you pick up animals and bring them to the ark. Sometimes you've got to lure the animals with hay or knock them out cold to get them on board. The one really inspired game mechanic (referenced in the book's cover) is that you can stack multiple animals--so as Old Man Noah you can hoist horses and cows over your head and still run at a full clip back to the ark.

Unlike the other two games, which can be completed pretty quickly, "Noah" takes forever. It's fun for a little while and then most of us give up around stage 3. I've heard Afronsky's Noah is overly long too. I guess epic apocalyptic stories like the Noah myth lend themselves to overstaying their welcome.

For the purposes of the book, are you playing the game on an emulator or do you have an actual copy of the game? I once played it over a few beers at Salvatore Pane's house in Indianapolis, so I've had a very small taste of the real thing.

I played the real thing as a kid but this year it's been on a Sega Genesis emulator. (it's got slightly better graphics than the NES version.)

My own NES is packed away at my dad's place or I would have bought a copy of Bible Adventures on eBay by now. The game sold well in its day so it's not hard to find a cheap copy of Bible Adventures. Bible Buffet and Sunday Funday are another story.

The description of the book for the Kickstarter campaign mentions "our retro obsession with 'bad games.'" What do you mean by that? What are some of your favorite infamously bad games?

There's now a pantheon of famous bad games. Shaq Fu, Superman 64. The most famous bad game of all time is E.T. for Atari. And we all have memories of when we bought cheap games with high hopes and were sad to see them fail us. I remember buying a game called Hybrid Heaven for N64--I couldn't believe how awful it was and that I was stuck with my poor choice.

In the book, I get into the fact that retro games collecting has created a weirdly inverted retro games market: Classics like the Mario games can be bought for cheap, but Bonk's Adventure for the NES goes for a lot of money now because nobody wanted it when it came out. Same goes for several Wisdom Tree games. This phenomenon partially explains the recent rerelease of Wisdom Tree's lone SNES game, Super 3D Noah's Ark--it offers collectors a new shot at checking an item off their list.

As the editor of Boss Fight Books, what's the game you're most surprised you haven't received a pitch for yet? Is there something that seems obviously to deserve this kind of treatment but hasn't been suggested yet?

Star Fox. Starcraft. Mario Paint. Wild Arms. Bust-a-Move. That drug dealer game for TI-83. I also haven't seen a pitch for League of Legends, the most popular game in the world.

To me, it's all about the author's take, though. Any game could make a great book or an awful one. Finding out what happens when we devote all this attention to a single cultural artifact is the big experiment and the big reward, so I'm trying to not get too hung up on HAVING to do books on certain games but instead finding the right game/author combos that will open the series up in exciting directions.

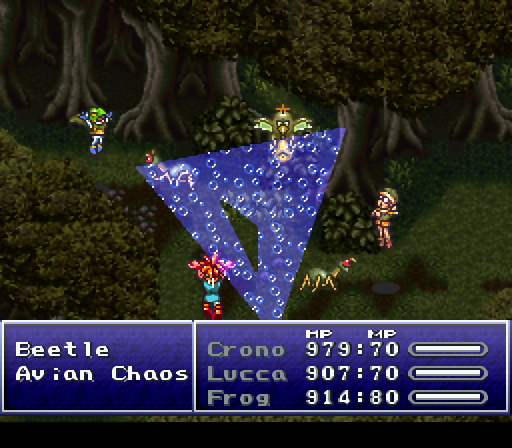

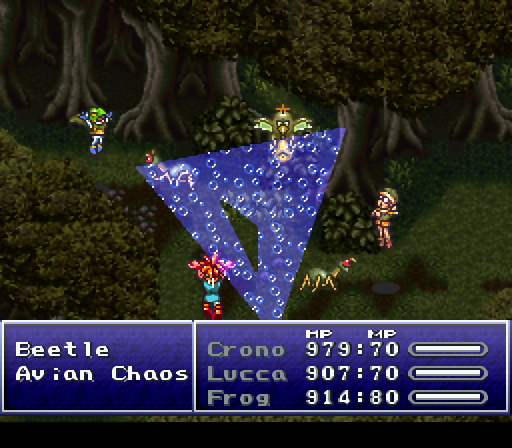

Since I started Boss Fight Books last summer, one of the biggest pleasures of running/editing “the 33 ⅓ of video games” was discovering Michael P. Williams. Boss Fight’s Kickstarter backers selected Chrono Trigger as the game they most wanted to read a book about, and when I put out a call to writers for Chrono pitches, it was Michael’s that blew me away.

What sealed it was a three-hour phone “interview” about Chrono Trigger, Dragonball Z, Secret of Mana, Japanese culture, and I think maybe the Star Wars prequels. My question, “Could this guy I’ve never met write a whole book about Chrono Trigger?” was more than answered. Michael’s writing is energized by a deep curiosity, a willingness to delve into his subject, to take Chrono Trigger as seriously as possible, and have a blast while doing it.

Case in point: In this interview, I asked him a dumb question about Spekkio, one of Chrono Trigger’s minor NPCs, and found, to my delight, that he had plenty of thoughtful Spekkio commentary ready to go. When I emailed him, “That’s a better answer than I deserved,” he replied, “It's an answer I'd thought about too! I didn't get to do nearly enough NPC analysis but there was just no room. I could have written a whole chapter about them. Ah well! This'll have to do, in the expanded gaiden of my book.” I need to go look up gaiden, but already I’m into the idea.

Now that his book is written, edited, and published, I thought I’d interview Michael again--this time not for his job, but just for the fun of picking his brain one more time. - Gabe Durham

*

Gabe Durham: In what could be the most controversial part of the book, you DARE to criticize the game's time travel mechanics. What--in movies, games, books, pop culture, whatever--is an example of a time travel plot that really gets it right? And what's a time travel plot that is just garbage?

Time travel is general is always going to involve a bit of bullshitting! Stories that get too hung up on paradoxes end up being really cumbersome, smarmy, and sometimes plain old unfun. One of my favorite masterfully handled time travel stories has to be 12 Monkeys (I haven’t seen La Jetée, on which it was based). The finality of time, the merciless grip of causality—it just gets so much right. But it’s a dark movie. And as you approach the ending you feel the noose of the time loop tightening around you. It’s a really tense movie. But it’s not fun.

If I want to go with fun, I’d go with Futurama. While the show does have its share of flub-ups in continuity, it does treat time travel with both irreverence for its conventions and with respect for its possibilities. As the series progresses, for instance, we continually learn more about the 1999 life of protagonist Philip J. Fry, and the circumstances surrounding his importance to the space-time continuum. At first Fry’s coming to the 31st century is a bit of a comedic fluke, but later it seems that many events have conspired to make this happen. The most vulgarly amusing of these is Fry’s having sex with his own grandmother to become his own grand-father/son—a special kind of incest that renders his brain “special” (read: “often stupid”), making it the most powerful counterweapon in the universe against a species of intergalactic brains that want to destroy all of existence. While autograndparenting is only hinted at in Chrono Trigger, Futurama provides a hilarious parody of the classic Grandfather Paradox that cripples many other time travel stories.

Meanwhile, there are far too many time travel flops to list, but Martin Lawrence’s Black Knight strikes me as one that is potentially offensive on any number of levels. Its worst sin, however, is its predictable fish-out-of-water storyline, and it’s a stark contrast to Futurama’s successes with the same trope.

Your book pokes at Chrono Trigger from just about every angle you could think of: The Hero's Journey, gender, physics, translation, etc. Why do you think CT is so ripe for this approach? And were there other angles that you tried to pursue that didn't work out?

Michael P. Williams: Since Chrono Trigger was a game designed by the collective input of a huge team, it felt right to take an unapologetically “kitchen sink” approach to never analyzing and critiquing it. It didn’t feel like bad form to mix and match approaches—critical race theory, queer studies, traditional literary criticism, and whatever else I smushed in there—though this would have passed muster as a “research book.” I also knew this was going to be a grab bag of topics—the game is just too multifaceted and too diffusively authored to articulate a single auteur-like vision.

I originally did have the idea of making this more academic than it ended up being—using words like auteur, for example. But then I got both intimidated by what I didn’t know and by what I’d have to learn just to start the process of learning more. I didn’t want to get paralyzed by unknowledge, so I just dove in at a certain point, leaving many sources unchecked. I had to remind myself that I was emphatically not writing a dissertation on Chrono Trigger, and that therefore I didn’t need a thesis. When I tossed out trying to find a unifying principle to rectify the disparate content of the game, I was actually able to start really writing.

I had had the serendipitous foresight to pack the prospectus I originally pitched to Boss Fight Books with tons of topics. Then again, I had also had the dedicated madness to watching ten straight hours of Chrono Trigger playback videos on YouTube while scribbling down notes. Of the 70% or so that was legible, I ended up with a huge, messy list of potential ideas. This very loose collection of talking points eventually was reshaped into many of the final chapters of the book.

One of the pleasures of editing this book was watching your balance of lucidity and generosity as a critic. Who are some arts critics you admire? What are some venues/websites that are really killing it?

I have to admit I approached this with some virgin eyes. I am not a huge follower of criticism. In fact, I’m poorly read when it comes to current culture. I read the Onion A.V. Club sometimes, or maybe a book review now and then, but in general I try to experience the original and don’t often look for critical consensus, or outliers.

It’s funny to me, though, that I tend to only seek out reviews when I loathe something—I want to feel vindicated. Many of my Google searches have been formatted as “___ is terrible” or “I hate ___.” I’ve had many things to fill in those blanks, often TV shows and movies. I will list three for you: The Gilmore Girls, Buffy the Vampire Slayer (the TV series), and Sideways. I have always found at least one excoriating review to justify my viewerly ire.

Something you don't get into in the book: What do you make of Spekkio? It always feels like a weird power play when Spekkio, before gifting the power of magic to the Future Saviors of the Earth, makes them walk around the room three times. Also, if his level of power matches whomever is in the room with him, what does he look like when alone?

Spekkio is a unique character in that, we have no idea what he really looks like. He's sort of like the lightbulb in the fridge, or the tree falling in the unheard woods—we can only guess what face he shows when he is showing anyone his face. Skilled players might be able to meet Spekkio in his weakest form, a small froggy. Most players will first encounter him as a furry kilwala, a kind of rabbit-ape. And as your party's lead character gets stronger, so do Spekkio's six distinct forms. His final form might be the toughest enemy in the entire game.

I think his major function is to serve as a friendly foe, a kind of constantly upgrading Gato—the karaoke battlebot that you can fight early on in the game. He's a way to test your skills in a relatively risk-free place, and if you can best him, you can earn limited-supply power-ups. Spekkio then fulfills a limited "coliseum" function—a feature which was never fully integrated into Chrono Trigger except by hackers.

As a character, Spekkio's major contribution is to unlock our characters' latent magic talents, and to hint at the development of magic in the world. Since he tells us prehistoric Ayla cannot use magic, we can make some guesses that magic was an invention of the Zeal Kingdom siphoning off Lavos's powers, else it was a wild card that Lavos introduced into the human population and that Zeal learned to exploit. We also know from Spekkio's housemate Gaspar that other visitors had been popping up in the End of Time, so whether these people got powers unlocked is an open question for fanfic writers to answer.

I like to think of Spekkio as more a trickster than an asshole, and his little game of walking his chamber thrice-deasil is a way to humble the characters rather than humiliate them—sort of like a Zen master making students sweep floors, maybe? Maybe also helps prepare the characters to accept the absurdity of magic. Even Hogwarts kids probably laughed the first time they said some Latinish gibberish and a spirit animal appeared. Without a sense of humor, ultimate power can lead people down a dark path.

By the way, according to the Japanese guide Chrono Trigger: Ultimania, you can actually trick Spekkio into believing you've traveled the room three times by following a weird, zigzag path. I admit I accidentally exited the room a few times trying to hug the walls, but this frustration of having to start over again can generously be read as an extension of the Zen analogy. Try, try again! And curse at the screen a bit too.

You successfully tracked down both Chrono Trigger's SNES translator/localizer Ted Woolsey and DS retranslator Tom Slattery for the book, and you read up on countless interviews in both Japanese and English with the game's developers. What about the game's creation surprised you? Did anything ever burst the bubble of what you'd assumed the creation of CT must have been like?

Oh, yeah! I’m like a bloodhound with these things. I was surprised how accessible both Ted and Tom were, and so willing to answer my questions. I even tracked down the only copy of Ted’s master’s thesis, and found it had surprising connections to Chrono Trigger. It was like experiencing my own personal synchronicity, and it was incredibly inspiring. I’m sure Ted was a bit spooked by my stalkiness there, but I think he was also glad to receive a PDF scan of an early opus.

As far as the creation of the game, I was surprised by how little the “Dream Team”—the three major producers and creators of the game—had to do with the game. The sheer amount of uncredited effort by people like Masato Katō—who wrote a good chunk of the game—and Yasunori Mitsuda—whose music many of us can still hum in the shower—was astounding. Granted, both guys’ names appear in the credits, but Mitsuda got totally snubbed in the so called “Developer’s Ending”—instead of him, it’s Nobuo Uematsu, who barely scored half a track for the game. I call bullshit on Japan’s hierarchical respect there.

Disappointments like these, however, were strongly offset by gems of esoterica, like the fact that Frog would probably have originally been “Spider,” or that the game was sort of the best leftovers of a failed Secret of Mana prototype. In the end, it’s always good to take a peek behind the curtain—even the humbug Wizard of Oz had plenty of cool shit to give away, floating head or not.

You wrote this book pretty quickly! I had this unique experience of getting to serialize your first draft as you were writing it, getting a new chapter every few weeks. What was your regimen like? And did we awaken a bookwriting beast that lurked within you all along?

The beast had always been lurking, and he was hungry! You just gave it something else to eat—though I assure you, many a cookie was consumed during the writing process.

After the initial research phase—which was a whirlwind two month process of gathering and compiling sources in English and Japanese—I started trying to flesh out the outline I had had in mind since the initial pitch. I started writing these chapters in book outline order, thinking I could keep the running train of thought on track. It became clear to me soon, though, that I was actually writing not a continuous narrative, but rather a series of interdependent chapters that could each be individual essays, if not for some transitioning thoughts that I later inserted to make the book flow more naturally. So, I’d have an idea for a theme, start taking notes. The notes would become a chapter outline, and then finally feel structured.

My library was a great place to work. It’s so quiet there—but not deathly quiet! The ambient soundtrack of shoes on the hard linoleum; soft, insistent coughing in the distance; the sound of dry, hushed laughter in a seminar room—all of these were incredibly relaxing. Often I would just sip my coffee and start pounding the keyboard, connecting the dots of the outline basically. There were some points when I was so in the zone that I would finish a whole subchapter in less than an hour. So, I guess part of my speed was having the right writing environment. Plus, being surrounded by knowledge was not just gratifying, it was incredibly useful! Articles and books for reference were often literally at my fingertips, so I didn’t really need to put many things on hold while I waited for sources to back up my writing.

More practically: as the bookwriting beast had just emerged, it needed some training. I really wanted to make this book good. I have to say, as fueled as I was by Ken’s EarthBound excerpt on Kotaku, I was also intimidated by the skill of his wordsmithing. Writing something both longform and creatively scholarly was a foreign concept to me, so following the deadline of having a first draft by Spring 2014—we originally had aimed for a Summer 2014 release—I created my own “halfth draft” deadline of Christmas 2013. I just wanted to get everything I had in for an initial pass through before even attempting a solid “first draft,” which was completed much sooner than anticipated. Looking back, these fractional draft numbers were probably confusing—I did call my individual chapter submissions “zeroth drafts”!—but this was also a manifestation of my fear of “this isn’t good enough yet.”

I still feel this a bit. In fact, I’m sure I will never not find a fault with any edition of Chrono Trigger—or anything else I write—but at some point you have to let these things go out into the world and succeed and/or fail! I’m confident that after all the hard work we’ve put into Chrono Trigger—and despite any typos or omissions— it’s exactly the kind of book I wanted it to become.

This is the fourth in our author-vs.-author Boss Fight Q&A series. Both Sebastian's book on Final Fantasy VI and Gabe's book on Majora's Mask are funding now on Kickstarter.

This is the fourth in our author-vs.-author Boss Fight Q&A series. Both Sebastian's book on Final Fantasy VI and Gabe's book on Majora's Mask are funding now on Kickstarter.